On many levels this has proved a difficult post to write – technically, professionally and emotionally. It is tricky to write about something that wasn’t: a non-fictional person who never existed. I say ‘non-fictional’ because a child is created before it is conceived. I don’t know who said this (please let me know if you do), but speaking from my own experience and from listening to the experiences of others, the potential child can exist as a powerful entity in one’s mind even when the physical child is absent. So, what happens when that ‘child-in-mind’ never gets to exist in reality? How do we grieve? What do we grieve? And how can we learn to live with the loss of a being that never got to be?

Trying to find a shape for the grief

Until I met my husband, I’m not aware of having an imagined or potential child. All I had was a vague idea that (of course!) I would have a child or children one day. I raced through my twenties avoiding pregnancy as though a child would be the biggest mistake I could possibly make. (Oh, the irony!) But it never once occurred to me that I wouldn’t, some day, have at least one child. For some people the potential child exists from very early on – perhaps even from their own childhood. Some people have a picture in their mind of what their child would look like and may have chosen a name or names. Whenever and however we imagine the imagined child, they can embody so many hopes, desires and dreams.

I didn’t have a picture of our potential child, rather a sense of what he or she would be like. Our potential child represented the living evidence of what my husband and I created both individually and together – our skills and talents, our relationship, our home, our families and our genetic lines. Once we decided to stop fertility treatment and to live without children, the list of losses that emerged from the non-existence of our potential child ranged from the obvious to the obscure, from the totally understandable to the irrational. My sense of loss was visceral and completely overwhelming. There was an emptiness that seemed to extend into the future. If I tried to articulate this sense of loss often the only words I could find were, ‘I feel so lonely.’ What was clear to me then, and now, is that I had no outlet for this grief, no terms of reference, no cultural or social framework upon which to lay my grief and try to find a shape for it.

The struggle to find an ending or a ritual overtook me. There had to be some way for our loss to be acknowledged and recognised. But how to explain to others? How to describe a child that didn’t exist? This silence, this inability to say that I. Have. Lost. became a torrent of un-cryable tears and unutterable words. So, I collected stones from the beach – they represented embryos we had created, including that final one we miscarried. It was ‘irrational’. But it seemed to come from a very primeval part of me – and it was a comfort.

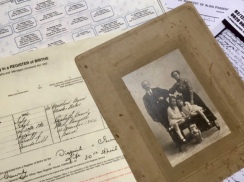

One of the more obscure effects of the loss of our potential child was a sense of responsibility to our genetic lines. At the time of our decision to end treatment I became obsessed with tracing my family tree. Looking back now I wonder if I felt that because I couldn’t produce forebears, I needed to find connections to my ancestors – delving ever deeper into the past. So one of the less obvious losses I felt was that I was unable to continue my and my husband’s genetic lines – lines that had defied so many hardships and horrors – potato famine, cholera outbreaks, Spanish flu, the Holocaust. With every new search or discovery, I felt my ancestors standing behind me breathing down my neck. The day the huge scroll-like document of my family tree arrived by courier, I honestly felt as though my house was crowded by a bunch of judgemental ghosts. At the time it seemed that having a child would have made all their hardships, successes and hard-won survival worth it. I felt ashamed that the genetic chain broke at my name – my branch of my family tree dangling like an empty hanger.

Finding expression and comfort

It surprises me is that there is so little written about the imagined or potential child. If you do an online search for ‘loss and infertility’ there is a multitude of academic papers and personal accounts. Do a search for something like ‘potential child and loss’ and very little appears. Perhaps the potential child is just too ethereal or maybe the loss is too difficult to pin down. Once the initial stages of grief have dissipated, it can be difficult to admit to anyone that you are still living with a sense of your potential child. As with so much about infertility and childlessness, the potential child embodies the invisible nature of our losses. Defining and describing those losses can be a bit like trying to grab a sunbeam. Enter the power of the poem!

A couple of years ago I came across a poem called Immaterial by Lois Williams in Mslexia Magazine that took my breath away. It began: In the drab half-hour/before the office closes,/or, sometimes, late at night/I think of them, the children/I didn’t have and tried to – …

You can find the rest of the poem here.

For me, the poem beautifully encapsulates the feeling that my imagined child is still with me in so many seemingly mundane moments and yet, somehow, I dare not even imagine how it would feel being the mother I could have been; that motherhood is a place I am not able to inhabit.

A couple of years after we ended treatment, I was trying to articulate some of these thoughts and feelings about our potential child to someone I knew. They suggested that I write a letter to the child I never had. I know the suggestion came from a caring place and was intended to be helpful but I was furious. ‘How could I write to a child that never existed?’ I thought. I know the unsent letter can often be a very helpful and therapeutic way of exploring some difficult emotions and it is used as an aid to thinking about unutterable feelings of loss. (There is a beautiful example of such a letter here). But I was totally paralysed at the thought of writing such a letter. For me it seemed to miss the point. There was no child – that was the point. I also felt that a letter that described all my hopes and desires for the child-that-never-was seemed almost to negate that child’s unique and un-measurable potential. But maybe, just maybe, to make the potential visible, to put words on a page, to make the unutterable loss a physical thing by turning it into a letter was just a step too far for me. It still is.

What did emerge out of the suggestion of the unsent letter was a poem – not about our imagined child but about potential. Science had offered us so much hope. There was so much about fertility treatment that encompassed the notion of ‘what was possible’ that I found myself writing my own formula for potential.

Living with the presence of absence

So now, 15 years on, what has happened to our potential child? If I were talking from the perfect world of ‘Completely Over It’ I would say that child simply faded over time. But I can’t say that. I still look at the empty branch beneath my name on my family tree and mourn that lost opportunity. I still watch my husband play guitar, I lift my pen to write, I sing in the shower and wonder if our child would have carried some of the essence of who we are. There are still moments when I can’t quite believe we will not meet our imagined child…and that he or she will never know us. I grieve for the small every-day moments as well as the momentous milestones we would have shared. But, and here’s the important and hopeful thing, it doesn’t hurt in the same way as it did before. It’s an ache that is heavier on some days than on others. But it is an ache I carry gently and with more openness and kindness than I did in those early days of grief.

So our potential child has lived with me for a long time but I never named her or him and I could never quite picture them. It’s not like living with a ghost or a haunting – more like living with a presence – a small, beautiful presence that sometimes tugs at my skirt, passes me on the stairs, reaches out for me in the early hours of the morning when the house is at its quietest. At times it is unbearable, heart-breaking. At other moments my potential child is a shining meteor that I can only glimpse from the corner of my eye.

Over the years, I’ve become used to this presence, grown accustomed to the unexpected moments in which I feel it most keenly. At one time I looked forward to the day that I wouldn’t feel our potential child’s presence anymore. But now I can say, that my potential child embodies not just those past hopes and dreams but the way in which my husband and I navigated such a life-changing loss. Most importantly, I feel that by making space for my potential child’s presence, allowing it to be a part of my life, I am honouring that loss.

I found a journal article, when researching for an essay on perinatal loss, that talked about the gap in literature about perinatal loss in general but also how it included the loss of potential-the writers suggestion for this lack was feminist writers were wary of writing about this in case it opened up too big a debate with those who are anti-abortion.

A lot of people struggle to understand the loss of a potential child. Thanks for sharing x

LikeLike

Thank you for this – really interesting. I can see how the idea of the potential child could be merged with the idea of ‘potential life’. I do feel that they are different concepts and as you’ve said a lot of people struggle to come to terms with the loss of the dreamed-of-child. I also think it’s wider than potential child – potential family, potential parents, potential life… There’s a gap in the literature perhaps?! Thanks so much for commenting.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yeah it’s definitely wider than potential child – potential future, hopes and dreams.

LikeLiked by 1 person